(excerpt)

There were days when not a single tourist came with the ferry from the other bank, the several metres of road on the deck of the ferry joining the actual road on dry land with a final clunk, at most a single car coming home to Ash Valley or a tractor dragging a red or green cage for sheep getting off. I sat behind the till of the souvenir shop, staring at length out the window and watching the cold showers sweep over the Lithuanian guest workers in their waterproof clothes, the dragon-like stave church, the grass, trees, and shrubs. The umbrella under which I took the one or two tourists who did turn up, their hair plastered to their heads and soaked to the skin, round, generally sat furled up in the corner, a cold puddle gathering under its downturned point.

Until now, I’d had on over my dark trousers only the uniform t-shirt of the Ministry of Cultural Heritage with the red anchor embroidered on the chest. Now I put my only warm piece of clothing on over the t-shirt, the woollen jumper with the silver clasps that I had been given by the missionaries in Cotonou. Unni, when he saw it, shook his head and noted – in his slightly reproachful dialect – that this was, sadly, against regulations. He fetched a black Ministry of Cultural Heritage cloth vest on its hanger from the storeroom, which was the standard issue for cooler weather. That was what I had to wear. The vest did not cover my arms, which were covered in goosebumps all day from the cold. But I didn’t mind. I found myself more or less enjoying the constant little shiver that I felt because of the prolonged, unusual, feeling of cold.

The last tourists of the season arrived in a silver BMW. Their car drove right up to where the stave church used to be and parked just outside the window of the souvenir shop. Which is to say, right in from of my nose, and next to the winch with which the Lithuanian guest workers were moving the bits of the stone foundations, each weighing several hundred kilos.

It was at that point that one of the regular showers swept out of Ash Valley. The sun came out and it turned out that it had, in fact, been sitting up there in the middle of the sky, shining all along. This northern sun seemed much bigger than the sun at the Equator, but it gave less heat. In that moment, it nonetheless flared with such exceptional heat in between two endless seas of clouds that the grass, trees, and shrubs, dripping garlands of watery drops, began to steam, as did the waterproofs of the Lithuanian guest workers. For a half an hour, the northern summer was back, for the final time that year.

The engine of the silver BMW stopped. For a long moment, the car fell silent and just gleamed. The big, plain surfaces reflected the sunshine. When the doors opened, refracted beams of light criss-crossed everywhere. It was so sparkly, it was as if some treasure chest of lore had opened. A family emerged from the blinding light. Mother, father, an eight-year-old boy and girl, and – as a fifth member – the grandmother. The father was wearing a comfortably creased yellowish summer suit, the mother a tutu that floated almost ethereally around her thighs in places. The boy and the girl were exceedingly beautiful, and the grandmother lively and young. All of them smiling and fresh. As it later transpired, they had come from Bergen, beside the sea, to spend the weekend; they went on long hikes and, out of nostalgia for the Viking past, had visited a few stave churches along the Sogne fjord.

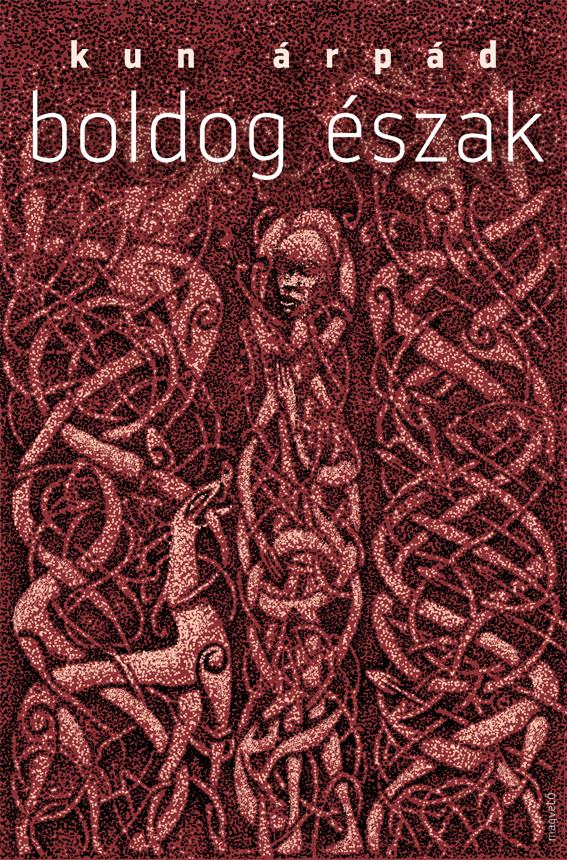

They paid close attention during my tour, nodding seriously, and asking me intelligent questions. Only the northern facade of the Ash Valley church was not faced with a protective covering. This was so that you could see the relief of the dragon, the Viking weapons and the Black figure. While the other sides were protected from the elements by a faded light brown layer of planks, the original plank wall was not covered on the northern side. This was the only place you could see that the nine hundred year-old wood was black as pitch from the pine tar it had been periodically treated with, and which it had absorbed.

I concluded my tour at the northern wall, in front of the relief, with these final tourists of the season, just as I had with everyone else before them. I recounted the story I had told a hundred times before mechanically, about Leif Eriksson and the other Vikings’ battle with the dragon that legend had it was the origin of the church.

I fished out the 20 Krone piece from the pocket of the cloth vest, with the portrait of the Norwegian King Harald V on one side and the motifs from the relief on the Ash Valley church on the other, including the human figure that I used to say – exaggerating somewhat – was me.

I was all set for the usual surprise, but it was in fact me who was lost for words.

The sun was shining at an angle that made the planks blackened by the pine tar retreat into shadow, while the family from Bergen were in the light. All of them – mother, father, the two children and the grandmother were straw blond, with milk-white skin and barely visible, reddish freckles. In that moment they glittered before me on the light side as if they had descended from somewhere on high as the counterweight to the dark, ancient struggle on the relief, from a pure, immaculate world.

In my new life, which began after my grandfather lowered me down on a rope from the great baobab tree in Dassa-Zoumé, I was much happier than in the former one. And the question as to whether I, as mixed-race, belonged among the Blacks or the Whites, never even occurred to me. Because of my European-ness, it had always been obvious to me that despite the colour of my skin, it was more to the latter. But in Europe, I was faced with the very opposite of this, which is to say that I was Black after all. And now I felt a pain in my heart, watching this family bathed in light. The shadow of some rare spirit fell upon me, because it occurred to me that only perfectly white, milk-white, people could be truly happy. Especially if they were Norwegian and come from Bergen to hike along the Sorge fjord.

Translated by Thomas Cooper